The term “specimen” is used in the sense of an example of use of a trademark. All trademarks must be appropriately used in order to qualify for, and in order to maintain, a registration. The purpose of a specimen is to show the Trademark Office that you have properly used the trademark. Thus, a specimen is not merely an example of the trademark itself, but is instead an example of how the trademark is used on or in conjunction with the goods or services for which the trademark is (or is to be) registered.

Most importantly, the specimen must show the Trademark Office that your use of the trademark is consistent with the various “use” requirements. Briefly, these requirements are: 1) the use must be in interstate or international commerce, 2) the trademark must be used on or in connection with the goods or services, 3) the use must be on the same goods or services specified in the application or registration, 4) the trademark used must be the exact same trademark as shown in the application or registration, and 5) the use must be a “trademark” use, i.e., as a brand or source identifier.

In most situations, the specimen itself is easily prepared. You can just take a digital picture of your use of the trademark on your product and email the picture to us. We will let you know if the specimen is acceptable.

Note that it is not acceptable to fabricate, mock-up or simulate a use of the trademark. The specimen must be an example of how the trademark is actually used on the goods or in conjunction with the services in commerce.

If the trademark is not actually used directly on the product, or if the trademark is for a service, you can send an example of how you use the trademark when the product or service is sold or delivered to the customer. We can work with almost any graphical file format (JPEG, PDF, GIF, TIFF, etc.).

An acceptable specimen must show the mark as it is actually used on or in connection with the goods in commerce. Ideally, a trademark specimen should be a label, tag, or container for the goods, or a display associated with the goods. In most cases, where the trademark is applied to the goods or the containers for the goods by means of labels, a label is an acceptable specimen.

Shipping or mailing labels may be accepted if they are affixed to the goods or to the containers for the goods and if proper trademark usage is shown. Shipping or mailing labels are not acceptable if the mark as shown is merely used as a trade name (the name for a business) and not as a trademark. An example of this is the use of the term solely in an address.

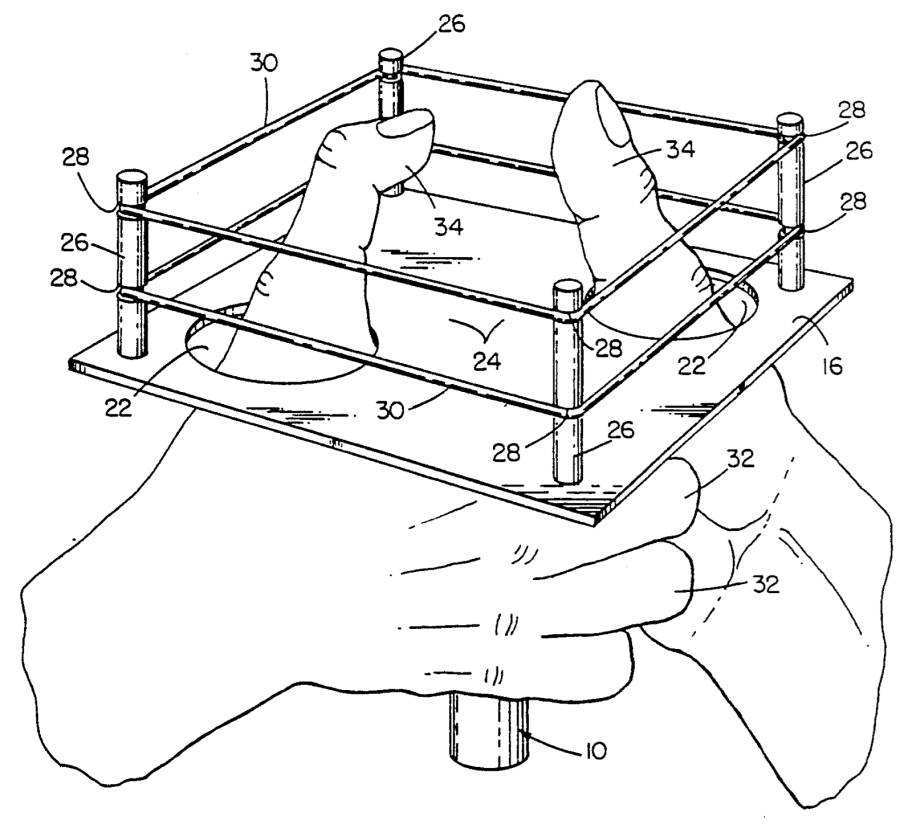

Stamping a trademark on the goods, on the container, or on tags or labels attached to the goods or containers, is a proper method of trademark use. The trademark may be imprinted in the body of the goods, as with metal stamping, it may be applied by a rubber stamp or it may be inked on by using a stencil or template.

The terminology “applied to the containers for the goods” means applied to any type of commercial packaging that is normal for the particular goods as they move in trade. Thus, a showing of the trademark on the normal commercial package for the particular goods is an acceptable specimen. For example, gasoline pumps are normal containers or “packaging” for gasoline. A specimen showing use of the trademark on a vehicle in which the goods are marketed to the relevant purchasers may constitute use of the mark on a container for the goods, if this is the normal mode of use of a mark for the particular goods.

For goods or services marketed on the Internet, you may submit a specimen that shows use of the mark on an Internet website. Such a specimen is acceptable for goods only if it provides sufficient information to enable the user to download or purchase the goods from the website. If the website simply advertises the goods without providing a way to purchase it, the specimen is unacceptable.

For a display to constitute an acceptable use of the trademark, the display must be associated directly with the goods offered for sale. It must bear the trademark prominently. Displays associated with the goods essentially comprise point-of-sale material, such as banners, window displays, menus and similar devices.

Such a display must be designed to catch the attention of purchasers and prospective purchasers as an inducement to make a sale. Further, the display must prominently display the trademark in question and associate it with, or relate it to, the goods. The display must be related to the sale of the goods such that an association of the two is inevitable.

Folders and brochures that describe goods and their characteristics, or serve as advertising literature, are not acceptable “displays” by themselves. In order to rely on such materials as specimens, you must submit evidence of point-of-sale presentation.

In appropriate cases, catalog specimens are acceptable specimens of trademark use. Such a specimen is only acceptable if: 1) it includes a picture of the relevant goods, 2) it shows the mark sufficiently near the picture of the goods to associate the mark with the goods, and 3) it includes the information necessary to order the goods (e.g., an order form, or a phone number, mailing address, or e-mail address for placing orders).

However, the mere inclusion of a phone number, Internet address and/or mailing address on an advertisement describing the product is not in itself sufficient to meet the criteria for a display associated with the goods. There must be an offer to accept orders or instructions on how to place an order. However, it is not necessary that the specimen list the price of the goods.

As discussed above, a website page that displays a product, and provides a means of ordering the product, can constitute a “display associated with the goods,” as long as the mark appears on the web page in a manner in which the mark is associated with the goods, and the web page provides a means for ordering the goods. Such uses are not merely advertising, because in addition to showing the goods, they provide a link for ordering the goods. In effect, the website is an electronic retail store, and the web page is a store display or banner which encourages the consumer to buy the product. A consumer using the link on the web page to purchase the goods is the equivalent of a consumer seeing a store display and taking the item to the cashier in a store to purchase it. The web page is thus a point of sale display by which an actual sale is made.

However, an Internet web page that merely provides information about the goods, but does not provide a means of ordering them, is viewed as promotional material, which is not acceptable to show trademark use on goods. Merely providing a link to the websites of online distributors is not sufficient. There must be a means of ordering the goods directly from your web page, such as a telephone number for placing orders or an online ordering process. The mark must also be displayed on the web page in a manner in which customers will easily recognize it is a trademark, rather than as something else (e.g., an address, the name of a business, information, etc.).

If printed matter included with the goods functions as a part of the goods, such as a manual that is part of a kit for assembling the product, then placement of the mark on that printed matter does show use on the goods. However, in this case, the instruction manual must be as much a part of your goods as are the various parts that are used to build the goods.

The Trademark Office may accept another document related to the goods or the sale of the goods when it is not possible to place the mark on the goods, packaging, or displays associated with the goods. This is strictly limited, however, and is not intended as a general alternative to submitting labels, tags, containers or displays associated with the goods — it applies only to situations in which the nature of the goods makes use on these items impracticable. For example, it may be impracticable to place the mark on the goods or packaging for items such as natural gas, grain that is sold in bulk, or chemicals that are transported only in tanker cars.

Advertising

Advertising material is generally not acceptable as a specimen for goods. Any material whose function is merely to tell the prospective purchaser about the goods, or to promote the sale of the goods, is unacceptable to support trademark use. Similarly, informational inserts are generally not acceptable to show trademark use.

The following types of items are generally considered advertising, and unless they comprise point-of-sale material, are not acceptable as specimens of use on goods: advertising circulars and brochures, price lists, announcements, publicity releases, listings in trade directories and business cards.

Moreover, material used to conduct your internal business is unacceptable as a specimen of use on goods. These materials include all papers whose sole function is to carry out your business dealings, such as invoices, bill heads, waybills, warranties and business stationery (e.g., letterhead).

Bags and other packaging materials bearing the name of a retail store and used by the store merely for packaging items of sold merchandise are not acceptable to show trademark use for the products sold by the store (e.g., bags supplied at a cash register). When used in this manner, the name merely identifies the store.

If material inserted in a package with the goods is merely advertising material, then it is not acceptable as a specimen of use on or in connection with the goods. Material that is only advertising does not necessarily cease to be advertising because it is placed inside a package.

Package inserts such as invoices, announcements, order forms, bills of lading, leaflets, brochures, printed advertising material, circulars, publicity releases, and the like are not acceptable specimens to show use on goods.

Service Marks

A service mark specimen “must show the mark as actually used in the sale or advertising of the services,” and the specimen “must show an association between the mark and the services for which registration is sought.” The mark must be used in such a manner that it would be readily perceived as identifying the source of the services. The specimen should at least mention the services, and show use of the trademark in direct association with the services.